As a student of geology, one of the first lessons you learn about your field is that geologic time is very different from everyday time as you experience it. Geologic time is measured in units virtually impossible to comprehend. The history of the Earth is measured in thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, hundreds of millions and billions of years. These numbers are so big that they can be hard to relate to. How can we, as beings whose lifespans are measured in such measly numbers as tens of years, even try to understand the history of a planet whose history reaches back 4.56 billion years? Or a universe that stretches back 13.7 billion years? Hell I don’t know. A year can feel like a long time. Even as a person who studies this stuff I can hardly wrap my head around the numbers thrown around when discussing any part of the planet’s past.

As Earth scientists, we have a system of dating that ties geological strata to time that we use to contextualize the timing and relationships of different phenomena as they occurred during Earth’s history. This is called the geologic time scale. This system organizes time into various units based on events that occurred in each period. Some of the units you’ve probably heard before, most likely the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous. These geologic periods contain the time when dinosaurs roamed the planet. The boundaries of these units are typically defined by major changes in global stratigraphic compositions indicating major geological/paleontological events such as mass extinctions. Here is one representation of the time scale:

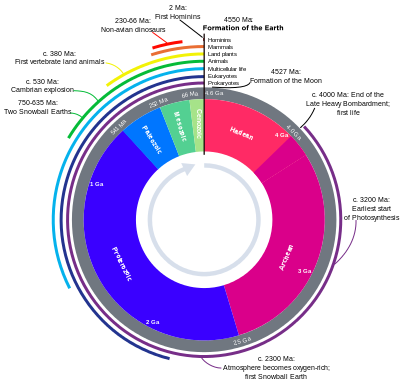

Clock representation of the geologic time scale shamelessly ripped from Wikipedia.

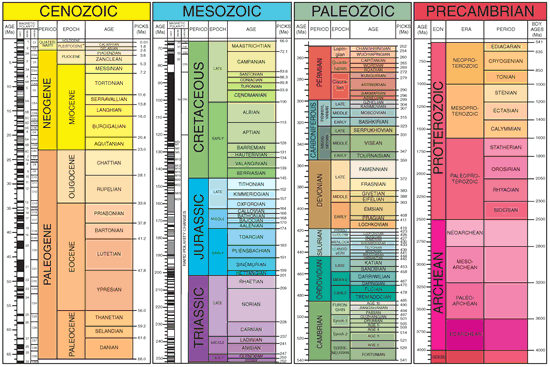

Here’s another:

A more traditional representation taken from the Geological Society of America.

As you can see, the geologic time scale is quite complicated and contains a lot of information. These representations attempt to represent the history of Earth in a compact, concise guide that is useful in contextualizing the aging of the Earth. It contains the histories of almost an almost innumerable numbers of species, many of which are not even found in the sedimentary record and thus not known to us. To use as reference, there are an estimated one trillion species of microbes on Earth right now, 99.999% of which haven’t been discovered. Not to mention the estimated 8.7 million species of eukaryotes (more complex organisms) that live on Earth right now as well. To imagine the number of species that have ever inhabited this planet is like trying to count the number of waves in the ocean. Or, most likely, to try to count all the waves in all the oceans on all the planets of the universe.

Prior to studying geology, meaning much of high school pretty much, my main intellectual passion was the study of history. Human history, that is. In particular I was primarily intrigued by modern Western/ Middle Eastern military history. The time period most of my reading was focused on was from 1700 onward. This meant that pretty much most of what I learned about the world outside of classes was in a pretty narrow, three hundred year window. I read histories of the American Civil War, World Wars I and II, the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, as well as many others. In my junior year I even found the time to read a fantastic three-volume biography of Winston Churchill that I highly recommend.

While I found the study of human history to be super fascinating, it didn’t prepare me all that well for my pivot into the study of geology. Pretty much the oldest thing I could conceptualize was Neolithic Revolution about 12,500 years ago. Now, for the everyday person it is pretty normal to think that 12,500 years is a very distant time in the past. So much has happened in human history since then that its very easy to cast out much of it and say its not super important to learn about. For me, the past three hundred years contained most of the important things that have happened in the world, and thus figured pretty highly in the way that I understood the society I lived in.

Once I began at university and was first introduced to the study of deep time, of geologic time, I was pretty taken aback. Of course I had already learned during my time in pre-college education that the Earth was billions of years old, but learning about the sheer amount of change that occurred during those billions of years really made an impression on me. Honestly, it brought a badly needed sense of perspective on just how little time that humanity has has existed. I guess you could say being confronted not only with the size of the universe, but also the age of it really forced me to confront my anthropocentric view of existence. We haven’t been around that long in the grand scheme of things, and if we don’t learn to extend our thinking past the short-term we may not be around that much longer.